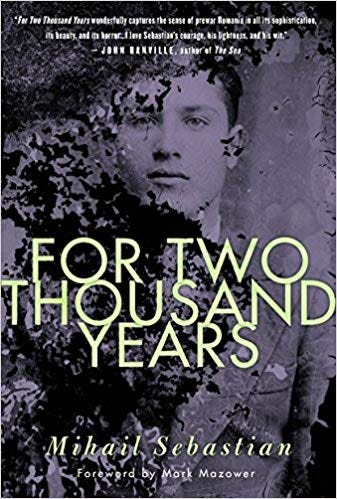

I am an odd reader. I read dozens of books simultaneously, over years. For almost a year I have been sporadically reading For Two Thousand Years by Mihail Sebastian. If I had to tell you what it was about, I would mentally flail about for a few seconds before mumbling, “It tries to answer the Jewish Question.”

Yes, it has a plot. But, to me, and the reason I can never seem to read more than a few pages at a time, the book is a startling reminder that we are helpless to truly fathom the force of the historic tides that change the lives not only of individuals but of nations.

Writing in the early 1930’s, Sebastian grapples with the ebb and flow of European antisemitism, with the rising roar of Zionists from East to West, with the nature of being an Other in a country struggling to find its own identity, a Romania straddling the widening gap between the Great Powers of the interwar years.

And yet, when he writes,

He's not a lunatic, or a metaphysician, or crippled with doubt, or poisoned by complex intellectual crises. To not be all these things, and yet be a Jew – there's a challenge.

It doesn’t sound all that different from the challenge facing modern Jews in the 21st century.

When he complains of the false sense of confidence in the air at his university,

We're in a stupid year, a year of prosperity. I'm waiting for the crisis. That's when everything will fall, be overturned. There's too much money around now, too much excess, too much optimism.

It doesn’t sound all that different from a university student today, as the stock market breaks records disconnected from the economic reality, as CNBC and Fox News continue to sell the lies of a corporate class uninterested in the worsening conditions of hourly employees.

But then there are lines that feel verboten today. Lines that remind you of why Primo Levi was unpopular with survivors and their descendants, why he never fit with the remembrance industry that sprung up to fill the many voids left after Hitler tore apart the festering wound of WWI’s inhumanity, leaving scars we still nurture.

More than once I envied the simple life of the ghetto Jew, wearing his yellow patch. A humiliating idea perhaps, but comfortable and clear-cut, because they had finally put an end to the horrible comedy of uttering their own name like a denunciation.

Sebastian could not know of the horrors to come. My own safta in Czernowitz, awarded to Romania after the Great War, and in her time in Tours could not believe how quickly the vocalized hatred turned into action across Europe. Unlikes my sabas on both sides, her family did not accurately assess the danger until it was too late.

How could any contemporary believe the reports, even when they were corroborated by relatives, friends, and acquaintances? We can ask that today. And yet we, too, are lying to ourselves.

Why should it be that great a leap to go from kidnapping children away from their parents and disciplining them by restraining them to chairs with bags over their heads to systematically murdering those we view as less-than?

We are living in the midst of terrifying times. Sure, some of our civic infrastructure remains. But, as Sebastian’s book paints so clearly, it did not all turn overnight. There were even years when Jews thought the worst was over.

As we commemorate the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, let us never forget that we were warned 85 years ago, and yet tens of millions of souls were murdered and starved and bombed.

If we are to avoid repeating history, we cannot be satisfied with good enough. We cannot be placated with half-measures. We must demand better, every day, for each and every human, and for the planet we are lucky enough to be stewards of.